|

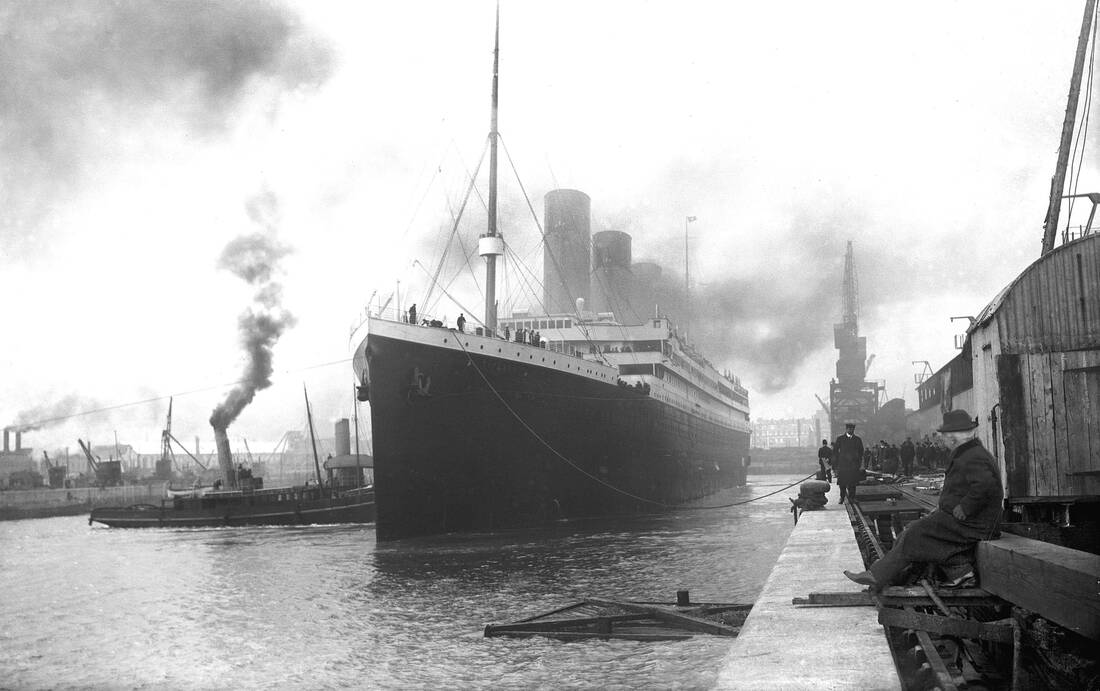

Today is the 110th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic.

We are all passengers now on a vast technological apparatus that is going under. It goes under slowly, unevenly. Parts of it, paradoxically, are lifted temporarily high in the air, by the dynamic instability of a structure in crisis. Rising to dizzying heights, some first-class passengers experience a temporary exhilaration, not paying much attention to the frantic hammering from deep within the hull, or the faint distant splashing sounds of those already drowning. Those elevated few may amass huge fortunes; they dream of becoming immortal and of vacationing in outer space, for the brief time before the whole vessel breaks apart and disappears forever into the unreachable depths. Those who do not go down with the ship may find themselves in an environment about as hospitable as a North Atlantic ice field on an April night. There will be no Carpathia, however, steaming towards them to rescue survivors. Perhaps a few lifeboats, which had better be well provisioned. If you find yourselves on one, steer towards whatever land remains above water, and find a way to live there, together.

0 Comments

The 21st of December. The ground outside is frozen and bare. The cold cuts sharp, with no snow to soften its edge. The husks of last summer's flowers and grasses stand, immobile and inert. In a little more than an hour, at 12:28 pm Atlantic time, winter will officially begin. Ahead lie three months of variable cold, treacherous driving, bitter winds, snows that will drift up and obstruct the driveway and block the front and back doors of my house. The ocean inlet I see out my window, across the road, may freeze over, sealed beneath thick pans of ice. It is the killing time, the long silence we must, as a northern people, endure every year.

In two hours' time, my part of the earth will start tilting back towards the sun. Tomorrow's light will last slightly longer than today's. In thirteen weeks, there will be crocuses on the front lawn. The thought of crocuses, however, has no tangible substance at this moment, and little power to comfort. We who live in the shadow of winter have learned to push away thoughts of summer. For the winter half of the year, we cannot really grasp the concept of long, warm days. Walking down an icy sidewalk, I may know objectively that, six months earlier, this path was bordered by flowers, but it has no present reality to me. One might as well speak of dinosaurs that once walked this patch of ground. That was then. This is now. The reality is, it often does not help one survive the winter to be reminded of spring. To remember crocuses is to make the present situation more difficult to bear. It is cruel, perhaps; at the very least, it is in bad taste. Hope hurts. Resignation is easier to bear. * A few days ago, I was at a social gathering at my university. My partner and I were taking our leave, saying that we had a bus to catch. Oh, but there are taxi chits, someone says. The university provides them, prudently, to relieve those who have drunk alcohol of the temptation to drive their vehicles home. However, I am content to take public transit. This is hardly a noble sacrifice. We have bus passes, so we are not out of pocket. The bus from here to my home is generally at least as convenient as a taxi, and usually more so. Cabbies can take a long time to find their way to the campus, which is buried in an otherwise residential neighbourhood outside the main downtown. Sometimes taxis never show up at all, while one waits in the cold. The buses run on regular schedules; the automated transit line tells me that there is one leaving in ten minutes, just time for us to retrieve our coats and walk to the bus stop. The route is a direct one: even if a taxi left at the same moment, it might not arrive any faster. Wesley, as it turns out, will know the bus driver (as he often does), and that will be an occasion for pleasantries. The bus will be warm and brightly lit; it will drop us close to my front door. I could say all this, but it would take time (and my bus is waiting); the person pressing the taxi option would still not understand. Like most people here, they take for granted that the taxi is more pleasant and convenient, even though it may well be neither. To keep it simple, I cut to the crux of the matter. The bus trip has a much smaller carbon footprint. I note this, in words as few and as modest as I can summon, doing my best to mute any possible overtones of moral superiority. The other person mumbles something like "Good for you." Then, more forcefully and rather cheerfully, words to the effect that my environmentalism is a lost cause and that the human race has already dug its own grave: the planet is doomed. Merry Christmas. The planet may well be doomed—although neither they nor I, nor anyone else, really knows. Climate scientists do know, pretty definitely, that we have passed a tipping point and that, at the very least, we are in the early stages of a very difficult time, one of mass extinctions and severe environmental distress. But no one really knows if these are the end days, or the bottleneck through which our species must pass to achieve a state more fully deserving of being called human civilisation. If you consider the latter possibility to be pie-in-the-sky, consider what would have seemed a "realistic" assessment of the world's prospects from the perspective of, say, 1938. Fascism on the rise around the globe; Stalinism at its most brutally repressive in the Soviet Union; Western democracies in economic ruin; weak and indecisive in their resistance to totalitarianism. The following few years would be among the worst in human history, delivering the Holocaust, the destruction of much of Europe, mass suffering in China, and the advent of nuclear warfare. Who might have believed you, in 1938, if you had predicted that, twenty-five years thence, much of Europe would be peacefully joined in what would become the European Union, the Soviet Union would be experiencing a cultural thaw and an official process of de-Stalinisation, most of the colonised world would have achieved political independence from its colonisers, an unprecedented economic boom would have dramatically improved the living standards and material security of much of the world, and the disparity between rich and poor would have been reduced to its lowest level in recorded history? Not that I wish to suggest that the world of the early 1960s was a paradise on earth—but it certainly looked a hell of a lot better than what anyone in 1938 had any reason to expect to see a quarter of a century later. My point here is simply that we really do not know what the future holds. Writing off all hope, on the assumption that we know exactly where this is going, is not realism. It is an arrogant assumption. If someone told me that they or their spouse, or one of their children, was facing a potentially fatal illness, not many people would consider it an appropriate response for me to say, "Well, you/they are going to die. You may as well face it." It still astonishes me when people do not think twice about asserting, in the face of environmental concern, that all hope is lost. The assumption seems to be that, while we may care deeply for our immediate friends and family, we can reasonably be expected to be indifferent to, and have no great emotional investment in, the fate of our children's children, or the planet they will be living (or dying) on. In the recent conversation about buses and taxis, what struck me was how readily, even eagerly, the other person rejected any possibility of positive action. As if that were somehow good news: a way of dismissing concern, as if it were less painful to condemn our children, our culture, our planet—the most beautiful thing we know of in the entire universe—to an imminent and miserable end, than to entertain the thought that our present actions might have meaningful ethical consequences. That response—call it fatalism, pessimism, realism—seems to be the default setting of many I encounter. These are not callous, uncaring individuals: many are compassionate people, who consider themselves committed to social justice. Many have children whom they dearly love; sometimes grandchildren, or the prospect of same. Yet I hear them repeating certain phrases that abruptly cut off discussions about, and thus consideration of, what we are to do, in the present moment of peril. "I won't live to see it" is one of them. The human race won't live to see it, is another: our benighted race will go extinct and the planet will recover and go about its business without us, healing over the scars of our presence. "We're doomed," is it in a nutshell, usually delivered—and this I find very curious—with a neat finality that suggests, not distress, but satisfaction. There: that's settled. Now we can go on poisoning the world until our number comes up. * Fatalism, resignation, realism. These have almost a reassuring sound, compared with what they really signify: despair. Resignation suggests coming to a place of rest, of letting go of false hopes. Despair, on the other hand, is a free fall into fathomless sorrow. As an atheist pagan, I do not often find myself in agreement with Catholic doctrine, but I am in sympathy with it on one point: that the one unforgivable sin is despair. I am not talking about depression. Depression is a malady that afflicts many of us; there is no comfort in it, and no one would knowingly choose it. If you are depressed, then you have my deepest sympathy, and my hopes that you receive the support you need to recover. I am not talking about depression, but about despair as a chosen stance in relation to the world, however disguised it may be as "realism." Notably, this comfortable despair seems to be more characteristic of life in the "advanced" societies of the global North than it is of people who really have more proximate cause for despair. "Nothing can be done. We have no real power." is the litany of people cradled in privilege and surrounded by material comforts. The people in Libya making the harrowing decision to attempt a crossing of the Mediterranean in over-crowded boats are acting on the basis of an indomitable hope, that, if not their own lives, then those of their children, might somehow be redeemed from the crushing forces of neoliberal capitalism, colonialism, racism; that an escape can be effected. Such people cannot afford despair. Our culture, beneath its seductive surface of technological wizardry, its ever expanding universe of digital distraction, its ballooning (if ever more unequally distributed) material wealth, is a profoundly pessimistic one. A torrent of on-line gaming and 3d movies and cat videos ensures that we will not sit still for even one moment, long enough to gaze into the black hole at the centre of the party: the black hole of despair. If you are relatively materially secure, relatively functional, and able to smile and proceed calmly with your life, while saying complacently that there is no hope, then I agree with the church on this point: you are damned. And I'll be damned if I am going to put up with that shit. • As I have argued above, despair is not necessarily warranted. Either hope or despair may be supported by selective use of the available evidence. Neither is proven, nor disproven, definitively. However bad things may be, the possibility of positive change remains—if we do not dismissively foreclose that possibility, by not even allowing ourselves to consider what that possibility might look like—and what achieving it might demand of us. The question is not which position—hope or despair—is supported by objective evidence. The question is which position is worthy of caring human beings; of a truly and fully human life. Despair is not a foregone conclusion. So what is so attractive about despair—for those of us who can afford it? It's called letting ourselves off the hook. The alternative to despair is not a comfortable one. To choose hope is to commit ourselves to questioning every action we take, and considering its consequences for the biosphere and for our fellow human beings, including those not yet born. I am not suggesting that our choices are always clear or easily determined. I drove a car to reach the place where I began writing this essay. It will have cost the planet about 20 litres of gas, and the ensuing carbon dioxide, for me to have come here and then returned to my apartment in the city. I find myself turning this problem over in my head every time I get behind the wheel, considering what options I have to shift the field of my choices. I am not claiming that my choices are superior to yours. I am saying that we are all obliged to consider our choices, whether they are easy or not, and to consider them in the understanding that solutions to our collective problems just might be possible, if we are prepared to do the work. Hope hurts. It is much less comfortable than despair. For all we know, there may be a way out of this terrible corner we have painted ourselves into; it will not be an easy way, and it will take all of our strength, intelligence and moral courage. To put the problem aside as unsolvable is not an ethical option. Those of us with well heated houses will soon find ourselves wrapped in a snug blanket of snow, and perhaps a smug resignation to the comforts of winter. We are condemned, however, to the possibility of spring. There is a place on the Nova Scotian shore of the Bay of Fundy where my friend Jim and I like to go. It is isolated, takes some trouble to get to, and is a place where we typically cannot see another human being for several kilometres down the coast. An afternoon's walk down a slope through the woods, along the rocks of a mostly dry stream-bed, brings us out onto a wide, deep beach of rounded stones, or shingle.

The Bay of Fundy has the highest (and lowest) tides in the world. Twice a day, they rise and fall by as much as 16 metres, or 52 feet. The seafloor is shallow along that part of the coast, so when the tide recedes, it goes out a long, long way. The shingle in our special spot stretches up from the sea in a vast crescent punctuated by cliffy outcrops at either end. All sorts of sea-wrack collects at the upper slope of the shingle, just before it disappears into the forest. In past decades, this storm-tossed debris would have consisted of kelp torn up from the seafloor, crab carapaces picked over by seagulls, driftwood, wooden buoys and sisal ropes escaped from fishing nets. Today, the crest of the shingle is a continuous tangle of red and blue and yellow synthetic rope, plastic buoys, water and bleach bottles, plastic children's toys, buckets, tampon applicators, discarded bands used to hold shut lobsters' claws, bits of engines and yard furniture and god knows what, the vast majority of it made out of plastic. This haphazard macramé installation stands roughly two feet (60 cm) in height, up to ten feet (2 m) thick from front to back, and runs without interruption along the top ridge of the shoreline, along hundreds of kilometres of coast. This is not, sadly, unusual. There seems to be no place on earth where flotsam collects, now, that it is not composed largely of plastic waste. * Standard plastic objects do not break down into organically useful molecules. They disintegrate into bits called microplastics that end up in the soil and in the oceans, becoming chemically associated with metal, polychlorinated biphenyls, and other toxic contaminants before they are ingested by insects, fish, and other animals, working their way up the food chain until they end up in our own bodies.[i] * When I was seven, and living in Marion Bridge, Cape Breton, our mother made me and my brother lunches to bring to school. She would wrap a sandwich in wax paper, neatly folded and tucked in a way I can still do with my eyes closed. The sandwich would go in a brown paper bag, along with an apple or perhaps some cut-up carrots. When we had eaten our lunch, we might throw away an apple core, to rot in the fields and feed the next generation of produce. We would fold up the wax paper and the brown bag and carry them back home in our book bags. There, our mother would wipe the wax paper clean and use it again for the same purpose, until it became too worn to use again. The bag, likewise, would be used repeatedly. The exhausted wax paper would be balled up to clean the top of the wood stove that we cooked on, before it and the paper bag would go into the stove as kindling. Nothing from our school lunches ended up in the garbage. I was a curious and solitary child, and spent a lot of time poking around in wild and deserted places. I remember what local trash heaps looked like then. The most visible common items that did not quickly decompose were distinctive blue glass bottles that had held a product called Milk of Magnesia, which people ingested to settle upset stomachs. The predominance of Milk of Magnesia bottles in those middens was not evidence that rural Cape Bretoners were guzzling it the way we now swig bottled water. These were poor rural people, and what the blue bottles contained was costly medicine. It constituted the largest visible category of waste because almost nothing else came in non-refundable containers that did not easily lend themselves to other uses. Pop and milk both came in glass bottles that were returned for cash. Meats and cheeses came wrapped in heavy paper. Fruits and vegetables were sold loose, and carried home in paper bags (or ones made of cloth or string), or, if bought in bulk, came in wooden crates or baskets that would be re-used endlessly, until they broke down and were burned to cook and to heat homes. Ice cream came in little boxes made of stiff paper board that also made good kindling, once wiped clean (usually by eager childish tongues) and dried out. Around 1961, however, an innovation showed up at our local IGA store. It was ice cream in plastic tubs. The tubs were turquoise in colour - a hue strangely at odds with flavours limited to vanilla, chocolate, and Neapolitan. However, for a couple of years then, everything that possibly could be coloured turquoise, was. * In 2016, local media reported that an endangered leatherback turtle found washed up in Newfoundland had starved to death after swallowing a plastic bag.[ii] It has become a common occurrence. According to a report published in 2015, more than half the world's sea turtles have eaten plastic.[iii] Another study, presented to the World Economic Forum in 2016, reports that only 5% of plastic waste is effectively recycled. Forty percent ends up in landfills, and a third of it in oceanic and other ecosystems. By the year 2050, the report estimates, there will be more plastic in the world's oceans, by weight, than fish.[iv] * A generation before the appearance of the turquoise ice cream tubs, whatever grocery shoppers there were in Cape Breton would have ordered their purchases across a counter. By the early 1960s, modern grocery stores had made their appearance. The cashier entered the price of every item manually in a mechanical cash register, while a neatly dressed young man (the work was strictly gendered at the time) waited at the end of the belt to arrange your purchases in big strong kraft-paper bags, and, if you wished, to carry them out to your car. The procedure still took more time than its contemporary equivalent, and left plenty of space for eye contact, greetings, and exchanges of pleasantries with a person whose name you knew without reading their nametag, perhaps involving a discussion of the weather and how your mother was doing since her fall. Over my lifetime, grocery stores have gradually transformed the check-out into an assembly-line procedure, and persuaded their customers to perform that industrial work themselves. We have been trained to pick our own merchandise off the shelves, to bring it to the cash, to load it in a prescribed manner on the conveyor belt, where an electronic eye reads the bar codes and tells the electronic cash register what to charge our debit card. The transaction has become, in every sense, remote. We may tap our card without taking out our earbuds, or if we are old-fashioned, we may fumble with the touch pad, and juggle our cashback, our debit card, and the receipt, all while conscious of our fellow members of the consumer proletariat, lined up impatiently behind us waiting for us to move on and pack our own bags and get the hell out of there. Such is the consumer paradise unto which technology has delivered us. * The first Earth Day was celebrated on 22 April 1970, one month before my sixteenth birthday. I came of age during that earlier moment of cultural concern about ecological issues. Since the early 1970s, I have been doing my best not to use plastic bags. It made me unusual then. Four and a half decades later, I am sorry to say, it still makes me unusual. * My neighbourhood grocery - an Atlantic Superstore of the Canada-wide Loblaws chain - proclaims on its streetfront that it is a bagless store: the first in Nova Scotia. This claim to be bagless has to be qualified. True, the clerks do not bag your groceries at the checkout; if you have not brought your own, they can sell you black fabric tote bags made out of recycled pop bottles, splashily proclaiming themselves to be "green." Most people I know have a stash of such bags, which they remember only intermittently to carry with them, and which pile up in black heaps in the back of the closet until spring cleaning, when they are dumped in the garbage and end up in a landfill. Being "bagless" does not prevent the store's clerks from automatically re-bagging every piece of meat. I suppose the idea is to provide another layer of protection against contamination - but it seems like overkill, when each is already sheathed in shrink-wrap plastic and a styrofoam tray. I can remember a time, not so long ago, when the butcher cut your meat for you at his counter, and wrapped it in brown wax paper to take it home. For a culture cutting a murderous swath across the living earth that sustains us, we are curiously, and very selectively, averse to certain kinds of risk. In our daily transactions, we make little effort to calculate the health risks of contaminating the planet with plastic. Despite forty years of doing my best to avoid plastic bags, I still have more of them than I can use. Compulsive that I am, I often bring one with me to provide for the supposed need for extra hygienic protection. The challenge is to produce the bag early enough in the transaction, to alert the harried clerk that I don't want another, and to hope they will remember and not re-bag the item automatically. The clerk - most likely overworked and underpaid - is performing an industrial procedure under time pressure; one I have just complicated by asking them to diverge from the standard script. They already have to remember to ask me if I have a points card, or if I want to donate to the Children's Wish Foundation. There is vanishingly little scope for improvisation, never mind actual human interaction. Introducing a non-standard request into the mix just rattles the clerk and tries the patience of the people lined up behind me. * The other day I bought olives at the Superstore. I brought my own plastic tub - needless to say, I involuntarily posses a large supply of same - and a plastic bag to contain the inevitable drips. Momentarily distracted by the problem of how to pack my re-usable bags, I realised that the cashier had already bagged the olives container inside fresh plastic from the roll of it stationed at her elbow. I told her I didn't want that bag and had brought my own. With an annoyed scowl, she pulled the (still clean) bag off the olives and chucked it in the garbage pail under the counter. Quite possibly, my request came out in a testy tone that she could hear as abrupt and demanding. Her response certainly registered as an aggressive repudiation of my desire to keep one more bag out of the landfill, and rendered my effort meaningless, since the bag was thrown out anyway. I picked the discarded bag out of the garbage and unhappily took it home to re-use, leaving with a storm-cloud of frustration and one more bag than I had arrived with. There is so much wrong with this picture. The class exploitation that structures the encounter between me and the cashier, so that the only roles available to me are either compliant fellow worker, or fussy, imperious child of privilege making yet another demand upon her labour. The mechanisation of our respective labours, unpaid and underpaid, and of the interaction between us, effectively leaving no room to communicate in a civil way that I don't want a bag - never mind the reasons why. * Three weeks before my encounter at the Superstore, fifteen thousand scientists signed a "warning to humanity." "Soon it will be too late," they say, "to shift course away from our failing trajectory, and time is running out. We must recognize, in our day-to-day lives and in our governing institutions, that Earth with all its life is our only home." * The check-out system at the Superstore has an automated option for me to donate to fulfill the wishes of dying children. What it does not offer is a chance to take even the smallest of actions to try to keep our children, and the diseased and afflicted planet we are leaving for them, from dying in the first place. Notes [i] Elizabeth Grossman, "How Plastics from Your Clothes Can End up in Your Fish", Time, 15 Jan. 2015, http://time.com/3669084/plastics-pollution-fish/ [ii] Metro 13 August 2016; http://www.metronews.ca/news/canada/2016/08/13/endangered-turtle-found-dead-in-newfoundland-after-eating-plastic-rescue-group.html [iii] Rachel Feltman, "More than half the world's sea turtles have eaten plastic, new study claims." Washington Post, 15 September 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2015/09/15/more-than-half-the-worlds-sea-turtles-have-eaten-plastic-new-study-claims/ [iv]"Davos 2016: More plastic than fish in the sea by 2050, says Ellen MacArthur." Guardian, 19 January 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jan/19/more-plastic-than-fish-in-the-sea-by-2050-warns-ellen-macarthur |

AuthorRobin Metcalfe is a writer, activist and art professional. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed